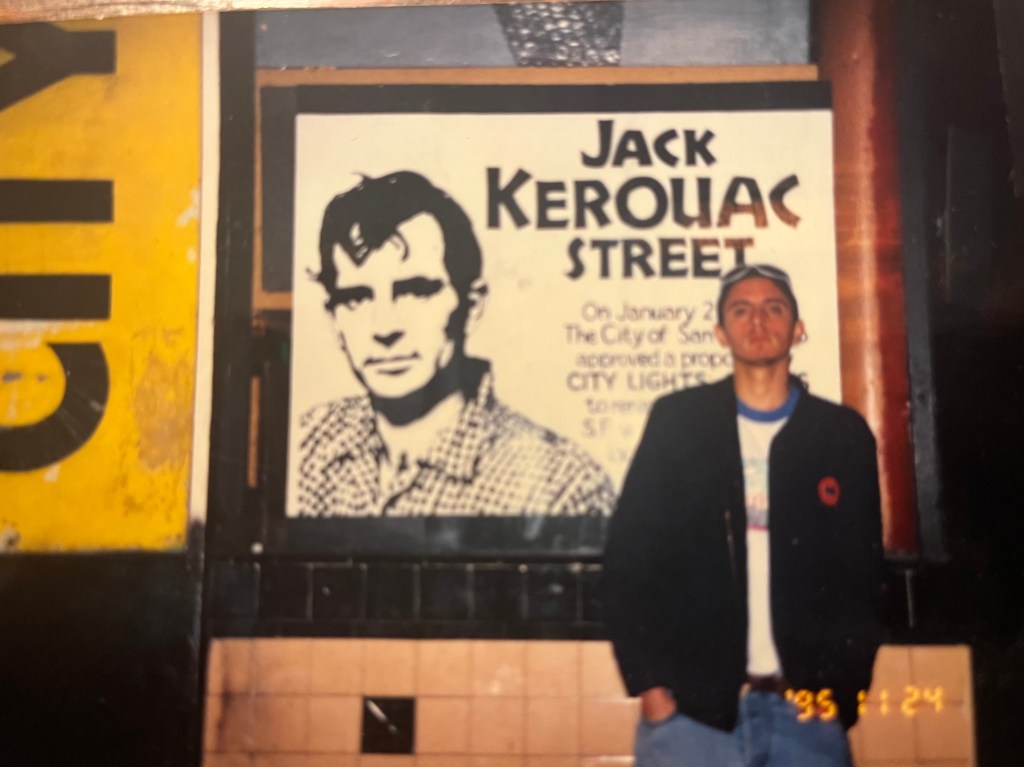

I spent a great deal of my twenties canned inside the dank sweaty armpit of travel Americana: Greyhound. My longstanding affair with Greyhound was born from a blended cocktail of economics and innate romanticism. As a young man with limited means at my disposal, bus travel was the most cost-efficient option. And my innate romanticism, which at the time constituted about ¾ of my psychic terrain, found its catalytic instigator and emissary in Jack Kerouac.

I had discovered Kerouac, by chance, when I was nineteen. I had been working as an editorial assistant at Families First, a parenting magazine located in Greenwich Village. One of my favorite things to do during lunch breaks was to pop into bookstores in the neighborhood—Strand, Shakespeare & Co., Barnes & Noble—or to browse the offerings of the booksellers lining the sidewalks. I had grown up in Bensonhurst, a working-class Brooklyn neighborhood, where I continued to live, but my integration into city life, and specifically Greenwich Village, had given me a whole new lens through which to perceive the world, and my place in it.

On that afternoon, I had gone to Tower Records, and on the lower level there was a section that carried a modest inventory of books and magazines. I saw the novel, On the Road, picked it up, read its back cover synopsis, and bought it. I had no idea who Jack Kerouac was, knew nothing about the Beat Generation. My reading selections up to that point, aside from that which had been assigned to me in school (and “assigned” reading material, no matter what it was, usually felt bereft of a certain joy, a certain curious warmth and timbre, than came to me when I picked or discovered books on my own, outside of school), had primarily been comic books, Choose-Your-Own Adventures, the Hardy Boys, horror stories, mysteries, crime novels, and serial killer biographies. My house was not in the least bit a literary one: my father read local newspapers and album liner notes, my mother read self-help books.

I started reading On the Road during my train ride back to Brooklyn, and as always happens with first love: its stamp was immediate and irrevocable. I zipped through the book in a couple of days and when I was done I was running a very high and happy fever. I was hot and giddy with inspiration. I was in that agreeably woozy state, which I would experience again later on with books like Tropic of Cancer (Henry Miller), Steppenwolf (Hermann Hesse), The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze (William Saroyan), and Ask the Dust (John Fante), in which I felt like my brain-breaths had been stopped in their tracks, or were in a state of exalted suspension. I hadn’t known writing could be like that: the velocity, the verve, the musical livingness of it. The language wasn’t just telling about and describing things, it was the thing itself, reflecting and exuding its womb-goo and exodus, its vital essence. And for me, who had spent a lot of time with Spider-Man and Joe Hardy and Charles Manson, this Kerouac was something brand-new and different, yet magnetically familiar.

Thoughts of traveling, of hitting the road had been ballooning inside me for several years, and Kerouac’s flood had broken me open. I felt ready to go. While my job at the magazine was a good one, with opportunities for advancement, I had discovered within my first month at the magazine that I had no desire to be a journalist, nor to climb the editorial ladder. I was obsessed with one thing: Experience. Experience, at the time, signified this magic abstract tangible, a matrimonial grail that if you quested hard and long enough, with the proper context of vision, you could find and hold and have. In a nutshell, my goal was to go out and find experience, as if accumulating pieces of gold, accumulate as much of it as you can, until you are filthy-rich with material. Then, convert your currency into words, into writing, and its value will be recognized and appreciated by the world-at-large.

Looking back at this nineteen-year-old, a wide-eyed babe greedily suckling Kerouac’s vision-engorged tit, throbbing with a sense of preordained destiny, I have to laugh, but my laugh is an easy and generous one. I’d root for this kid, and kids like him everywhere, any day. The beauty in foolishness is something that remains both legend and testament lodged warmly in my heart, and I hope I’m still saying that when I’m seventy, when I’m ninety, when I’m beyond marking the passage of time.