I.

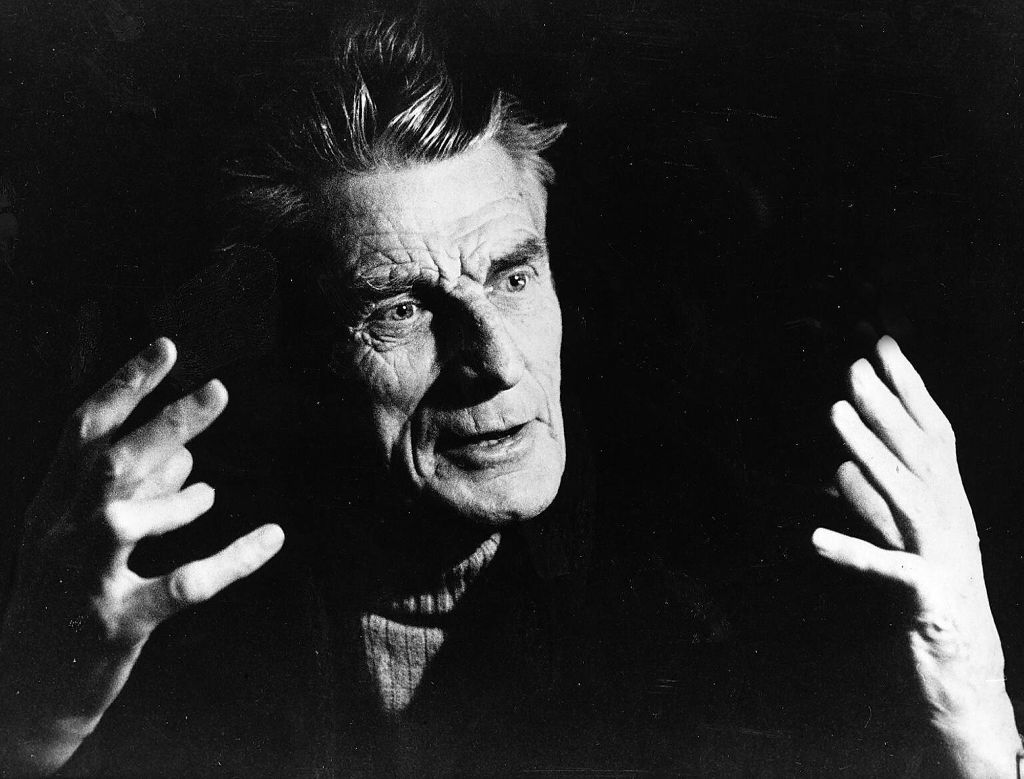

Beckett spoke about it: the inability to keep quiet. The incapacity to not say stories, not write stories, not place oneself inside stories in which you make and unmake and remake yourself endlessly, an orgy of particles constellating jittery shifts. Beckett, with death’s head irony and gallows brogue, talked often and plenty about silences. He attempted, through literary and theatrical practices, to reach silence, to braid and outline silence. He amassed spools of verbiage in his attempt to penetrate silence, to not say anything, to negate through words taking leave of themselves before settling as shadows. I will say a lot in not saying anything, or, I will say nothing in many words saying nothing. It was a calculated gambit rigged to fail.

II.

Everyone dreams according to their own schedule of being, their own silences and motives, their own sphinxes and disciples. Whether or not you want them to, the stories go on, they go on and on, a vast and inescapable network. Inside me they never stop. The narrative splinters into multiple narratives which splinter into further narratives, a hyper-exponential proliferation of narratives swaddled in recursion. In in, in there, I see myself and lose myself and find myself and wonder about wonder while wondering about myself: solipsism to the nth degree. There is no such thing as a writer who isn’t self-absorbed. Absorption-in-self is their stock and trade, their jurisdiction and wild frontier.

III.

We try and give voice to our silences because so much of us lives there unspoken. We barter fretfully with the unspoken.

IV.

Beckett attempted to reach the end of language through language. He found that dead ends were turnstiles, that vultures were morning doves in top hats. Beckett’s long sonata of the dead was the revival and impossible task he set for himself. He attempts to go beyond words by using words, like trying to starve oneself by gorging on excess amounts of food. You could say Beckett was a literary bulimic.

V.

Beckett tried to corral silence by making silence the domain of language. To not say anything, to ultimately embrace silence, would have meant an even more impossible task—setting down the pen, laying to rest the voice—and placing a moratorium on words. The only way Beckett imagined that could happen would have been through death. Death, flexing dominion, would have to pry the pen from Beckett’s cold stiff hand. Death would have to impose the silence and gag order that Beckett could not attain by choice. From out of smoldering and sepulchral silences words arise, only to immediately plunge back into the abyss. Gravity’s mouth, magnetic and godlike, is essentially a devourer of seasons. And words, trained through voice and causal urges, are always resisting gravity’s vortex just long enough to spell out hints, needs, cries for help and homesickness disguised as small dark birds. We come out of silence only to return there. Lots of words and stories and jig-dancing at night’s edge in between.

VI.

I have no desire to sing tonight.

This is the only line Samuel Beckett managed to write for a libretto which he abandoned.